Providencia, May 2018.

From Panama I sailed north, bound for the island of Providencia. The voyage was a success insofar as I arrived safely, but not otherwise. In defiance of the forecast the wind swung round to blow from the north, and blow hard. The current flowed south too, and more strongly than the pilot book suggested it would. This combination of wind and current from the north meant sailing north was a thankless task. My tacking angle flared to nearly 180° so I could sail east or west but not north. After hours of bashing into the seas hard on the wind on the starboard tack followed by hours more bashing away on the port tack I found myself pretty much where I’d been before. I continued to sail but turned on the engine and used it to sharpen my tacking angle so that I’d make at least some progress towards my destination.

The sea seemed bad tempered and unfriendly. Rain fell heavily from the grey sky, the big drops blown by the strong winds making time on deck unpleasant. Progress was slow and the boat’s motion uncomfortable. But that wasn’t the problem. The problem was the boat. Within hours of leaving Panama my towed generator packed up. There was no way I could repair it in those conditions, so I set it aside to be attended to once I arrived. I had three other means of generating electricity anyway: two alternators and my solar panels.

A few hours later the toilet broke. I could only flush it by throwing a bucket of seawater down it. Such is the romance of yachting. Then the fridge stopped working. On the pitching, rolling boat I could not see an obvious problem in either case so I added them to the list of things to be dealt with when I arrived. Next I found that my hand-held radio could not be charged and would not work, and added that to the list, too.

Then things got more serious. Moonrise has two alternators mounted on the engine rather than the single one that’s more usual. They’re secured in a bracket that attaches to the engine in the place where the one alternator for which the engine was designed would normally be. Perhaps the extra weight of the two alternators was to blame, or the increased strain from their drive belts, but whatever the cause, the piece of the cylinder head to which the alternators were attached simply broke off. This was a serious problem that would be difficult and expensive to fix. And, not only did I now only have one of the four methods of generating electricity I’d left with, the engine’s sea-water cooling was also out of action as it’s driven by the same drive belt as one of the alternators. This was bad.

Broken Engine Casing

Thrashing my way slowly northwards with 25 knots of headwinds, an adverse current and a growing list of failures it’s easy now to say with a wry smile that I felt somewhat beleaguered. But at the time it was not funny at all. The optimism with which I’d set out on what I’d hoped would be a pleasant voyage was replaced by a grim determination simply to get there in the face of bad conditions and a growing list of failures.

Despite everything, I did eventually arrive at Providencia, dropped anchor in the harbour and slept for eleven hours straight. The next day I put the cover back on the engine and didn’t look at it. I did ordinary things, like putting the sail covers on, cleaning the boat and checking-in with immigration. I wanted to rest and let some time pass in order to gain a proper perspective. I also made some minor repairs (including the toilet) in order to get some easy wins in the bag and regain some confidence that I can do this stuff.

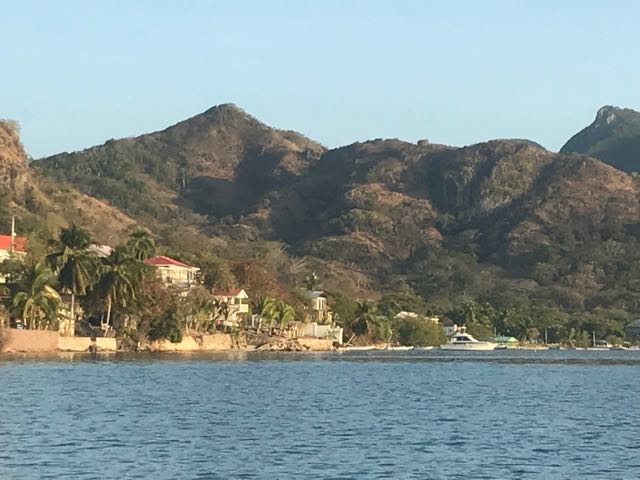

Providencia Anchorage

I reasoned that things were perhaps not as bad as they seemed. I can only carry a limited supply of spares for the toilet so I wait until it fails before servicing it. Failures are thus to be expected from time to time and it just so happened that it failed this week. That the walkie-talkie packed-up was not surprising either. I’ve had it so long that I was expecting it to die and had already bought a replacement ready for when it did. I didn’t know why the generator had stopped working but I thought I knew how to go about fixing it. I also didn’t know why the fridge had ground to a halt but it wasn’t a serious issue. For some time I’d been toying with the idea of living without it (for reasons that I’ll talk about another time) and while I’d have preferred to have decided to do so rather than to have my hand forced it was nonetheless something I’d been planning to do at some time anyway.

So, apart from the engine, most of the failures were individually not too bad. It was just unfortunate that they’d all happened at once. So my reasoning went. But mood and reason are not necessarily linked and besides, the engine problem was more difficult to wave away. There was the difficulty and expense of repairs, but also the fact that I was surprised by the failure.

It may be that by adding a second, high-powered alternator to the engine I had unwittingly over-stressed the engine casing. It’s this that shook my confidence rather. I had thought that what I did was was okay. In fact I’d thought it was rather good. But it wasn’t okay. This begs the question: how many other things are there that I think are okay but are in fact not okay at all and are waiting to fail? It’s a sobering thought.

I resisted the temptation to throw myself into a frenzy of engine repair activity. This was clearly going to be a long haul and it was important to keep the home fires burning. So in the mornings I continued to do what I always do in the mornings: charge all the batteries, turn over the eggs, sort through the fruit and veg to find any that are rotten before they affect the others, fill the water tanks, do the dishes, do the laundry, write my diary and, probably most importantly of all, sit in the shade with a mug of coffee, just looking at the scene around me.

In the afternoons I turned my attention to the engine. After two days I’d determined what spare parts I’d need. In three more I’d found some suppliers in America who had them. But it took another ten days to determine that there was no reliable way to get them from America to Providencia. There were a couple of options which “might work out” or would “probably be okay” but for hundreds of dollars worth of essential parts that didn’t seem to me to be good enough.

By good fortune (and I was surely due some of that) Ulrike and Matthias were in Mexico on their boat Bella and told me that the parts I needed were available there. So they bought them and sailed from Mexico to the Cayman Islands and, after a few days there, headed on south to Provodencia, bringing my precious parts with them.

While I waited for them I explored the island. Providencia is about 250 miles off the coast of Nicaragua. At only 7km long, and 22km2, it’s tiny. It was first settled in the mid 1600s by British Puritans but in 1670 the English pirate Henry Morgan (him again!) took over the island and used it as a base from which to raid the Spanish empire. His treasure is said still to be buried there. After that Providencia was ruled alternately by Spain and Britain for many years until, in 1822, it became a part of Colombia. It remains so to this day although the 5,000 people who live there are fiercely independent of spirit and several I met made little secret of their animosity towards their Colombian rulers.

Unless you have your own boat it’s a place that’s hard to get to so there isn’t that much tourism. What there is focuses on eco-tourism for the intrepid few willing to make the trip. The locals seem determined to protect their island and their way of life from the rampant development seen elsewhere. There are almost no cars. Everyone gets around by motor scooter. My introduction to this was on my first day ashore when I was checking-in. I was at the agent’s office where the Immigration Officer had just finished doing her thing with my passport and her forms. Next we needed to visit the Port Captain whose office is some distance from the agent’s. The Immigration Officer offered me a lift on her moto and we zoomed off at what seemed to me like break-neck speed, my shorts, T shirt and sun hat flapping wildly in the wind, my flip-flops slipping off the foot pegs. When we arrived she turned around and left again. Her business was completed at the agent’s office, it seemed. She was only being friendly by giving me a lift, which was really nice of her and I was grateful, but she scared me half to death in the process.

I hired a scooter of my own and rode it right round the island at a somewhat more sedate pace. The coast road is the only significant road on the island so it’s impossible to get lost. Almost all habitation is on the coast, too, so if you keep going for long enough you’ll get to anywhere you want to be. While I had the bike I went to the foot of the trail that leads up the highest hill on the island, parked it there, and walked to the top.

Mostly, though, my time was spent on normal things: trying to get my laundry dry, going ashore for groceries, that sort of thing. In the process, especially as I was there for so long, I got to know some of the locals a bit. This is always rewarding. I also got to know the few other sailors who stopped by the island. I played a lot of pool with the crews of two American boats who were there for a couple of weeks. Several cruisers said that Providencia was their favourite of all the Caribbean islands and I’m inclined to agree though being so quiet I’m sure it’s not to everyone’s taste.

The thread that holds together my canvas spray-hood and main-sail cover had perished in the tropical sun so, as I have no sewing machine, a great deal of re-stitching by hand was required. Sitting on deck in the sun, or in the cabin with rain drumming on the roof, sewing away, hour after hour, day after day, might seem like a tedious task. But focusing on a simple, repetitive task with my mind largely blank was perhaps the best thing I could do at that time. I felt better afterwards.

In due course Bella arrived with my precious parts. They turned out to be the right ones and within a few days I had the engine fixed, or at least returned to its former state with two alternators presumably over-stressing the engine casing. I’d also worked out by then what was wrong with my towed generator and that I could not fix it. But ashore I found a mechanic of quite stunning resourcefulness who, with the limited facilities at his disposal, was able to get it apart and replace the seized bearings. When the time came to pay we engaged in a bizarre sort of negotiation in which I tried to persuade him to accept more than the very modest fee, even by local standards, that he insisted upon despite the considerable time and effort he’d invested.

Matthias & Ulrike get a Taxi

I didn’t leave as soon as the engine was fixed but spent some more time on Providencia with Matthias and Ulrike. The island is either brilliant or boring, depending upon your taste. I really liked it. But after two months there, and with the hurricane season approaching, I sailed south again, bound once more for Panama. And wouldn’t you know it? The wind swung round to the south leaving me beating into head-seas again. The boat’s motion was strange for some reason and I was seasick to the extent that my navigation log is blank for long periods as spending more than a few seconds anywhere between lying in my bunk or sitting in the cockpit made me feel nauseous. Eventually I was sick, felt better, and resumed my normal sea-gong routine, though I didn’t eat at all for the first two days. In early June I arrived back at the familiar anchorage at Portobelo, Panama, that I’d left ten weeks before.

Leave a Reply